Introduction

Arindom Datta, Executive Director and Head of Rural & Development Banking/Advisory, Rabobank, has been working for Rabobank for the last 14 years and has over 28 years of experience in Rural Finance, Cooperative, Microfinance and Agribusiness banking. He is responsible for the sustainability banking initiatives on knowledge, risk management and business development. He also oversees the Rabo Foundation projects in blended finance, technology/innovation and access to finance in the agriculture sector. Arindom is further passionate about following the Agtech developments and its significance for small holder farmers. He previously worked with National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development, IDBI Bank and CARE. Arindom’s work is recognized and he has been honoured with the ‘India Sustainable Leadership’ award at the India Sustainability Leadership Summit in 2017.

His other affiliations include Independent Director of NABKISAN Finance Limited; Observer on the Board of Agrostar; Advisory member of Climate Smart Agri 100 of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development; Member of the FICCI Task force on Agtech; Member of the National Advisory Committee on the PRODUCE Fund for FPOs set up by NABARD

Q) Would like to start this conversation by understanding your views on how COVID-19 and the lockdowns in India have had an impact on the agriculture financing sector.

One of the winners, among various sectors, in terms of recovery post-COVID, is the agriculture sector. It has overall fared better than the other sectors – even if you look at the gross level. If you see it in terms of GDP, while in the last quarter, India’s GDP went down by 24%, which is a record low, agriculture showed a 3% increase. It needs to do well because irrespective of what kind of disruption you have, the food needs to move and people need to eat. Farmers have grown their crops, and the product needs to move to the market.

Despite this, we all know that there was much disruption during the lockdown because goods and people could not move. So obviously there was a hit, especially at the micro-level and in specific sub-sectors in agriculture. The most significant impact was in the HoReCa (hotel, restaurant and catering) segment where the food supply chains were geared up differently and, there was more institutional buying of food. With the lockdown, suddenly the HoReCa segment came to an abrupt standstill, and there was a significant disruption.

Second disruption and impact were in the non-food agricultural produce like cotton. If you look at the end-users of cotton, i.e. the garment manufacturers primarily, the demand for this has changed drastically. Suddenly it wasn’t essential any more, as there was a large stock existing in the market.

Q) Could you share your perspective on the global as well as Asia Pacific region faring in terms of the agriculture financing sector, in terms of recovering post-COVID?

So far as financing is concerned, I believe overall India has done a great job. A reason for this is because agriculture is a priority sector lending requirement, which is unique to India. As it is a massive chunk of the balance sheet of any bank, whether you are a Public or Private sector bank, it needs to go towards agriculture, and this has made financing stable in the Indian ecosystem.

Another reason is the pressure that is always there on policymakers, especially the government of India, to ensure that financing reaches out to the farmers. This pressure still exists and increases during a crisis. There were a series of meetings where the banks were coached that funding to the agriculture sector needs to continue. Many COVID schemes which came up were targeted towards SMEs, rural institutions, MFIs, NBFCs and other segments which provide a huge chunk of capital to the agriculture sector.

This scale of disruption was something we had never seen earlier. There was uncertainty about the existing moratorium once the crisis period was over – in both the microfinance and agriculture sectors. Collections are still taking place, and we’re unsure of how it is going, even though some institutions have done well.

Overall, so far, I believe we haven’t seen any red flags, but I think we need to wait till the end of this year or the beginning of 2021 to see how collections have stabilized.

I can say that, overall, agriculture financing hasn’t been a big problem in the Indian agriculture sector. But on the flip side, the general appetite of the banking sector to finance came down drastically because of the uncertainties caused by COVID. Banks weren’t sure how COVID would impact individual sectors, and so, initially, a lot of financial institutions had clammed up. Most of the financial institutions limited their financing to existing customers, i.e. the ones who they were familiar and comfortable with. They were not willing to take on new customers.

As per the statistics coming in, there was a bumper sowing during the Kharif season. The farmers benefitted from the financing received from different institutions which led to such bumper sowing. Overall, the jury is still out! We will have to wait till March-April of next year to see how the agriculture sector and the portfolios have been impacted and how.

Q) You mentioned that the general appetite of the banking sector came down initially post the lockdown – but based on the Kharif sowing – it indicates that both formal and informal financing has reached out. Assuming that the formal sector was initially hesitant to lend to farmers, does it mean the funding took place from traditional sectors? If yes, then how do we understand the efforts taken by institutional financing sectors, like banks, in building trust with farmers?

We have to wait for the granular data to come out to see how much of financing has happened during the first phase of COVID-19, one, vis-à-vis the previous years and two, vis-à-vis the amount of sowing that happened – we still don’t have those numbers. It is a little early to comment, but the general feeling is that a lesser amount of financing would have occurred because banks had lost their appetite.

With regards to the different initiatives by banks to build and ramp up their agricultural financing portfolio – I don’t see a significant challenge there. Agriculture, as we all know, is a large sector with 51% of the population involved directly or indirectly in it along with 135 million farmers. There is a temporary disruption for banks that are looking at growth in the agriculture sector. No bank has changed their agricultural financing policy so far. This is a seasonal blitz, and I would expect all banks and other NBFCs and MFIs to come back to their financing levels very soon. However, the challenge that we have before us is how do we make such institutions more resilient? How do we know that the shock experienced this year will not happen again?

I believe that technology will make the farmer more resilient by providing information about market access, location of the product and other logistics. Digitization and digital solutions have got a significant tailwind during the COVID period because, without them, the information asymmetry is too high for businesses to be resilient during a crisis period.

In the future, we would see considerable interest in making businesses more resilient, both from the financing as well as the market viewpoint. Technology will continue to play a significant role in the next few years, and businesses will adopt new methodologies to make their systems and their business more resilient.

Q) Resiliency is an important aspect but is still a big challenge, at least for farmers. I say this because, despite a bumper Kharif sowing, we had very unseasonal heavy rains in Karnataka, Telangana, Maharashtra. This damaged crops substantially. Despite all the efforts made by the entire sector to bounce back, it seems a lot of it gets eroded. In the future, do you see financial products – both loans and insurance – being diversified and contextualized enough to address these kinds of challenges that we see because of climate change?

It’s a little disappointing that climate risk hasn’t been incorporated by the financing systems in India so far.

The question is then how do we protect our client from the climate risk – whether they are farmers or small businesses in the Agri sector or any sector. How do we, as a financing institution, protect our portfolio from climate risk?

The immediate need is in the financial products, as you mentioned. The lending product is probably the only financial product in India that is doing better than the other emerging economies. This is because of policy interventions in institutions from the regional rural banks to public and private sector banks, and the MFIs. However, it is the insurance product that I would say is extremely weak in the Indian market.

Historically there has been no insurance product that has worked well in India. Our focus needs to be on integrating the weather risk, pest attacks and any other risks that a farmer might face and use it to build a product which would be viable from his/ her perspective as well as the insurance company’s perspective. I believe this would be possible with the intervention of technology.

If you see any insurance product, there are two overall costs – the granularity of the risk model, and the insurance premium payout. The insurance company has to understand how granular they need to get in understanding the risk of the product – where the higher the granularity in the risk model, the higher is the cost. There is also an inverse relationship between the premium payout and the risks involved. The less you spend on understanding what your chances are; you’ll land up paying more premium. But the more you spend on really understanding the risk, the less premium you will payout because you have covered your bases through the initial premium charged. However, doing this manually in a country as complex and diverse as India is incredibly challenging. That’s where technology has to come in.

We need to leverage the potential of technology to be able to do the granular number-crunching in a very cost-effective and detailed manner. We need to build up the knowledge through AI and Machine Learning mechanisms and come out with insurance credit modelling, and price modelling in a way that is more efficient.

As an agriculture banker, I am not happy or satisfied with the kind of efforts that have come out on the insurance product, even know private entities are making developments. There is potential for a lot more work, and I believe that without technology we will be back to square one. The technology practices we need to adopt will have to make sense of all the diverse information available. This will help to make very credible bet-taking on insurance products in different agro-climatic zones across parts of the world and India and for various commodities as well.

There is a significant lacuna in the Indian bouquet of financial services in the agriculture sector. It is a global issue as well in countries like Africa, South-East Asia or Latin America. But in India, because of the existing scale of fragmentation – we have to come up with a better solution, and if required, provide subsidy efficiently to mitigate risk at the farmer’s level.

A major challenge that I see looming ahead is the climate risk. It all starts with our ability to understand and work on two initiatives – one, where Indian farmers need to adapt to the changing weather patterns; and two, making the agricultural practice cleaner so that the mitigation strategies are in place. How does agriculture as a sector evolve so that it becomes as less of a polluter towards the climate?

There is a large bank of information out there, especially with the research institutions/academia doing specific studies like “climate-smart soya bean in Madhya Pradesh”, or “climate-smart practices during different sowing seasons”. Whether we are agricultural companies or sizeable corporate financing institutions, we are still learning how do we adapt and make our practice cleaner. I want to reiterate my point here that without a robust technology, this is just not possible.

A point that I would like to highlight here is – even though India is in a race to address climate risk concerns, I have a hope in India because of the number of small farmers we have. I believe that we can make small farmers change their agricultural practices quickly compared to the 100,000-hectare single commodity growing large farmer in the US, Brazil or Australia. But for a smallholder farmer, if they have the right knowledge, advisory, inputs and access to the markets, then they can easily switch from one crop to another depending on the climate factors – like soil and water availability.

If one tries to do this physically, it is going to be a nightmare with the knowledge getting lost in translation, from the research institution to the millions of farmers. It will not be sufficient unless we have the right kind of technology platform. Farmers can use this platform to tap into the right advise of what to grow and how to access the market and income opportunities, and where to get the required raw material. Many technology players are working towards this and researching into climate-smart agriculture. Without technology to enable this in a country like India, we can’t do it!

Q) How do you define the policy-making complexities or dichotomy, when it comes to the credit and insurance piece in the farm sector?

In India, we have seen that the government’s busy rolling out an insurance product which they are doing independently. The private sector players are building and rolling out their own products in the market – but it’s a very distorted market out there.

The two most significant issues in India still are – first, the interest rates where lending is concerned and second, the premium where insurance is concerned. Who is going to pay the premium – the farmer, or should it be subsidized? If we want to subsidize it, do we have an efficient manner of doing this? Would the government also fund the private sector schemes?

I believe that for different commodities in different agro-climatic zones, the actuarial studies should reflect what premium would make it a viable business for insurance providers. This, matched with the interest cost, will make the lenders build a profitable portfolio, and then also look at the farmer who pays a certain insurance percentage. Would such a cost-loaded model make sense for the farmer at the end of the day? It requires a comprehensive approach where all stakeholders need to get together and look at the entire ecosystem of cost and benefits – otherwise, it’s not going to work.

To answer your question – it is a distorted market as far as insurance is concerned. The government schemes are not working too well, and most of the farmers don’t seem to be too happy with it. Many cases have been reported where farmers have suffered a loss but haven’t got a compensation; and vice versa where farmers have been compensated even though they haven’t incurred a loss. A lot more work needs to be done there and again, and we need technology for all this!

The biggest bane for the financial sector – whether it’s insurance, transactions or financing or any other product – is the transaction and risk cost. How do we handle the transaction cost, and how do we control the risk cost? Both of them are immense when you’re dealing with a very dispersed and fragmented farmer base, and that’s where we need technology. The earlier we adopt it, the faster we can scale up, and the sooner the digitization of farmers can be taken care of – this is a complex issue at the moment. The good news is that with the existing technology, organizations are making small developments and are succeeding!

COVID is a new challenge; it’s happening today. But 25 to 30 years back, when I was starting my career – the same issues were being discussed. To ensure that 20 years later, we aren’t discussing the same problems, we need to ensure that they are taken care of by the adoption of technology.

Q)It’s interesting as the emphasis on technology is very important, and the impact isn’t felt in the diversification of financial products. For example, – you take traditional agri-credit products which have a limited effect on climate resilience. It doesn’t insulate the farmers from the vagaries of climate change; nor does it reduce the probability of repayment failure, thus making it highly risky. Do you think that there is a re-alignment of farm-credit risk beyond the insurance?

Absolutely! If you look at the way financing is done in the more matured markets, they are working directly with the customers. These are the large farmers with whom they are working on addressing climate risk – both from the bank and client’s side and protecting the portfolio. The banks will get hit if a farmer gets hit. Hence, they have to protect the farmers and help them on the sustainability journey by making them aware of the existing risks, the mitigants available and what they need to do to adapt.

In India, so far, climate risk has still not been incorporated in the financing decisions in the agriculture sector, as well as other sectors. However, in the Agri sector, banks must start incorporating and investing in people who have the knowledge and products which are climate-friendly, investing in clients to make business more robust and resilient.

I believe that with the kind of danger we are seeing for farmers and production and 'nutrition security' of the country – it is a matter of time before these practices are incorporated.

There exists a vast amount of knowledge, and we need to keep building this with customized data for different regions. Diverse conditions mean the existence of various factors, and the technology solutions need to address this.

Q) It is a big challenge! Despite having technology, there are banks which are still struggling to mitigate the risk on the portfolio because it’s not being utilized at a loan product level yet. They are using it to optimize their processes and reduce transaction costs. However, they’re not using this data to create new loan products in a manner that can cushion them from this risk or create new business models using the same technology to ensure them of this risk.

This issue that you have brought up hasn’t been seen in India alone, but also in regions like Latin America, Africa, South-East Asia. Let’s look at it from the perspective of any business – once you become a large organization – for you to become more agile and adopt technology for your benefit – becomes extremely difficult. We are seeing that across sectors, many big players are not embracing technology to sharpen their product, their businesses, their client base and services – and because of this, they lose out.

If you look at the agriculture or agriculture financing sector – there will be institutions which will do what you have stated. They will use all that knowledge, not only to build key products and services to make themselves better but to also adopt relevant risk mitigation measures.

Several banks, including some traditional ones, have started adopting technology for financing decisions. There is a shift taking place with new-age players like the AgFinTech companies who are leveraging their agility and broad knowledge base. With the help of advanced technologies at the back-end, they are building practical, efficient solutions which are better than the traditional ones. Such organizations are going to become critical players in the field of agriculture financing. If conventional banks don’t respond to the solutions which are out there by adopting them – they will be risking a lot and will not be able to sustain financially. The winners will be the ones who embrace technology, and through this, sharpen their products, especially with a focus on climate risk.

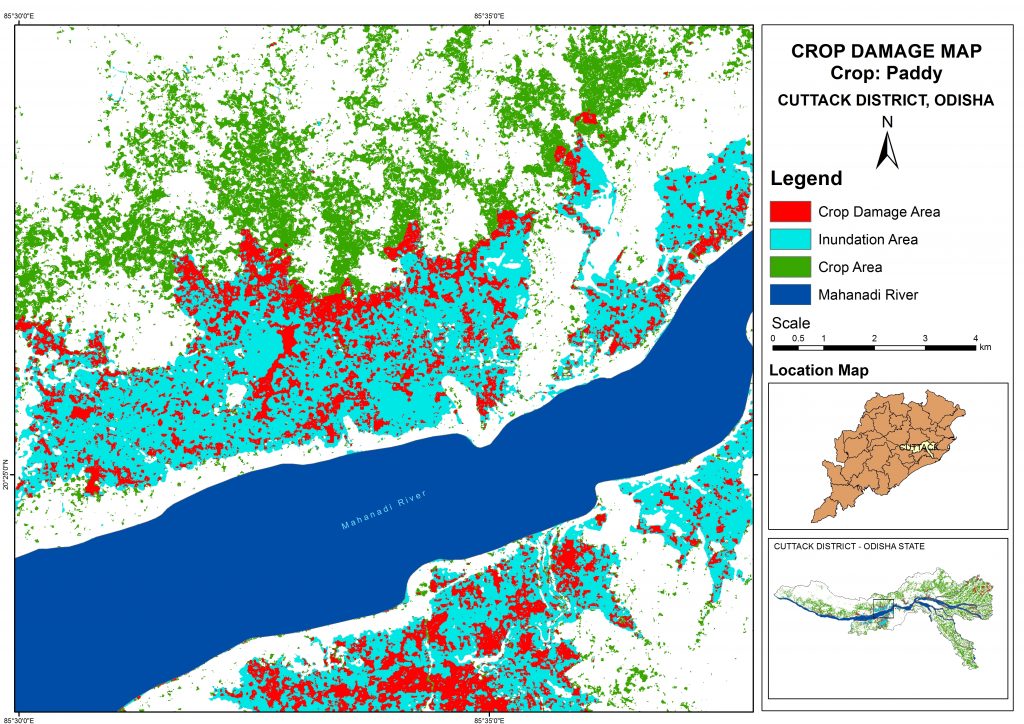

(Odisha), India (September, 2020)

Q) I agree. There are, however, several challenges with such technology as well, which one needs to be aware of. There are different categories of technology solutions which focus on credit access, advisories or providing a risk-management overview. This fundamental aspect of digitization in the farm sector is receiving a lot more optimism than pessimism. My question here is on the pessimism side.

What do you think is the moral and ethical canvas around which the technology adoption should happen because as a technology of this kind seeps into critical sectors of finance and agriculture – it is going to impact the lives of people. If today we’re making a credit decision based on trust and tomorrow it’s through a model, what mitigation steps should the banks and insurance sectors look at to avoid biases in the model that could be due to the data on which it is built?

While technology is set to be the next key enabler for addressing the opportunities and risks in the sector, there still are issues that we need to discuss. One is, as you mentioned – there will be haves and have nots. 30% of farmers have access to the most refined products and are categorized by the model as ‘good farmers’. There will be another 30% who will be excluded entirely from this model, and they may not even find out the reason for this. That’s where the question of the ethicality and universality of our technology comes up. Are you challenging it to be more inclusive by reaching out to all the potentials from a gender and region perspective? You would need to use the right kind of data points to build up an inclusive technology ecosystem. Policy frameworks at both the national and institutional level have to be worked on. How many of the banks’ sustainable initiatives lead to ESG goals (Environmental, Social and Governance) especially on the social front, of being more inclusive so far as the vast majority of the population is concerned?

The second biggest challenge is about data protection. How do we protect and manage all this data, who does it, what are the norms, the best practices and who supervises this entire sector? There are zillions of sensitive data points out there, and we need to protect them!

The third is about the redressal mechanism when something goes wrong. When you interface with technology and not a person, and something goes wrong, like a failure of the system – who will address it? In a physical system, you’re so used to walking into a branch and telling the branch manager that I have this problem and he’ll advise you on the path to take and to some extent that works. But let’s say I am a farmer in the future, and I have this gadget through which I am getting advice on transactions, and I encountered an error. Do I have a redressal mechanism out there which works instead of always saying “we’ll get back to you” and no one gets back!

These are the three broad areas where we need to work a lot and make changes. You will agree with me as a technology player that not everything is optimistic and right; there are issues which we need to tackle soon!

Q) These are very pertinent points, and the reason why I asked this question is that there aren’t enough people thinking this way or even how to address these issues. Strangely enough, there aren’t any policies or an RBI directive on how to efficiently move from a physical system to a digital one in agriculture.

You’re right. We have also observed that the European regulators and the Dutch Regulators, are coming out with robust requirements for climate and technology reporting. Like what data are you using, your model, how accurate is it and how customer friendly is it? These regulators are pushing very hard for such reporting to take place because it’s complicated to supervise technologies as they can be very disruptive for the existing system. So such regulators always need to be one step ahead, and this isn’t easy!

How does one regulate it in a manner that it is equitable, fair and incredibly customer-friendly? These are questions that regulators are raising – be it from the insurance, banking or other financial services sectors.

Q) My last question to you would be as a summary of the year 2020, through your lenses, what is some insight and overview you could provide of how you see us moving into the next decade, especially in comparison to the last decade and the last one year.

First, I would like to highlight that there have been significant developments of niche products which are ‘agri-smart’ and ‘climate-smart’ to support the agriculture sector in the years to come. Second is the presence of blended finance transactions in the industry. Blended finance will be using non-commercial and commercial capital to come up with a product which can take the necessary risks which need to be taken when trying to address a climate issue. These are on the rise – like, for example, in the education and health sector. Rabobank has launched a slew of blended finance products for FPOs, climate-smart agriculture and AgFinTech companies.

The third is about “green financing” or “sustainability linked loans” or “ESG compliant loans“. We see an increasing number of such loans globally including in Asia, where many banks are focusing on stepping up their sustainability compliance and performance. In a broad sense, we will see increased Green Financing not only in sectors like construction, transportation and housing but also increasingly in agriculture. We need to build such products or face a disaster in the future. We need to “green” our portfolios not for the sake of just reporting and recognition, but real greening where every financing has a positive impact on the environment and people. This will happen significantly in the years ahead as we have regulators and the youth pushing for more environmentally friendly products.

I hope that in the year ahead, using technology as a wild card, we can move more towards sustainable related financing options, and this will take place across several sectors.

Technology is an enabler in this journey of increasing efficiency and making businesses more resilient and robust in the years ahead. We need broad-based partnerships/collaboration as per SDG 17 to make technology not just an enabler but also a solution to increase sustainability in the years ahead.